|||

Emely had left when she was fourteen. She had left her sister in the bed, under the thin sheet. The cool blue air of morning, with the birds and the empty road. Under her sneakers, dust. Soft. Giving.

Emely breathed.

All the houses, all the streets. The mountains. She trailed her hand over the stucco walls as she walked. Kept close to the corners, out of the sun. Out of the open.

“No no, mijo. It was different.” His mother shook his head.

At the table, Arlin drank juice out of a plastic bag. They sold soda in bottles and cans in a closer store but he’d walked a few blocks, bought the bright pack instead. Naranjilla. Cheaper by fifty cents. It was sweet and runny, and he sucked in his cheeks. The kitchen was dark, it was mid afternoon.

His mother tapped out the rest of the coffee grinds into the trash, the clanging hard against an unpapered bin. “She took our cousin’s backpack without asking. It was bigger. She was stubborn.” Arlin’s ma sank against the counter, setting the tin coffee pot back on the stove. “Un testarudo. It was stupid.” Arlin could hear the implication in Mamá’s voice. The tk tk tk tk of the burner turning on. Emely would have rathered die than stay.

He glanced at the juice bag, now crumpled and deflated in his hand. Tia Emely had been raped. His mother didn’t have to tell him that.

|||

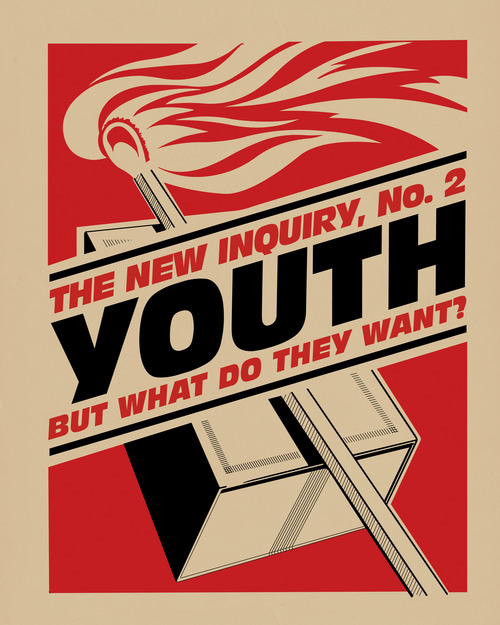

In the classroom, Stephany turned to him from behind her desk. “Hi,” she said, even though she knew Arlin spoke Spanish. It didn’t matter. She was taller, and whiter. She was fashionable for eighth grade. Had dyed a strip of her hair blue, wore Vans. Arlin wondered if she had a dad.

|||

“Jordan?” His teacher asked.

“Arlin,” he tried again.

“Aaron?” she said, haltingly. Her brow furrowed. She was young. She didn’t want to be wrong.

“Yes,” Arlin said, finally.

|||

Darrel, Emely’s brother, blamed it on los Yan-kees. “Fuck L.A.,” he told Arlin. He was drinking a beer on the couch, his sneakers kicked off. Arlin had tensed seeing the six-pack. “It’s the gringo’s fault,” Darrel swore. “They deported those fuckers. They sent them back.” Darrel’s neck moved with the fluid, a snake along his throat. He wiped his arm. “That made them stronger,” Darrel continued, into the cool, dark room. The TV droning. “The US,” he declared, “made them strong. They came back, picked people up like a bag of coka.” Arlin didn’t respond. Just watched the sun pass through the gold of the glass, the small square window cutting light around Darrel’s hand.

|||

Stephany’s chest fell from her body. She curved. Her jeans curved around her, snug on her ass, thighs, hips. When the teacher asked a question, she raised her hand. She tried answering. She was good at explaining. Even if she did still use the dictionary. She had already been here for a year and a half.

|||

There were four Indian boys in his class. No, one corrected him, I’m from Bangladesh. They’re from Pakistan. And Yeman, the other added.

Arlin nodded politely. He had never heard these names before. No. He thought about it quickly. Pakistan. He’d heard that one.

Two of them always raised their hands. They were always right. The other one talked constantly to the Taiwanese girl next to him. Arlin suspected flirting. The last dark-skinned boy stared ahead. He barely talked. He was the most handsome.

|||

Stephany introduced him to music. “No,” she said, when Arlin asked. “Actually it’s from here.”

She put the earphones carefully up to his ears, the tinny noise suddenly becoming clear. The buds were cheap.

Arlin hesitated and then kept walking with them in, Stephany silent beside him. They padded down the grey sidewalk, the vacant street. Tall brick walls. Rows of windows. Everything in New York was the same. It was quieter than he had imagined.

Arlin listened to the familiar reggaeton drums, softening now, now rising. His feet memorized the turns. Memorized the blocks.

The lyrics were in Spanish, but Arlin already sensed it: American-raised Latinos were different.

|||

Another girl came to the school after Arlin. Her name was Salma. Salma sat at front of the class. She wore long, draping robes and pinned fabric to her forehead. Her skin was the color of ash. She had a narrow face and large eyes that loomed out of it. An elegant nose, a little bulb dew-drop at the end that reminded Arlin of the slender-stemmed cebollino, always young when pulled from the ground. Her lips were dark and soft and when she stood up he could see how skinny she was. She was a ghost, a bobblehead. Had long, tapering fingers and didn’t cut the nails, not in the stylish way. They were naked and plain. She repeated back the phrases to the teacher. She smiled. Salma reminded him of the word selva. Jungle.

. In her, he tried to find the Aladdin he knew from Mamá’s tattered children’s book. The pictures still vivid. As a child Arlin had loved it, had changed the captions, the story of the images. The book had originally been Emely’s.

|||

When both his neighbors left, Arlin played soccer in the lot behind the houses. The dust rolling up with the ball, a long strip of sky. Little plastic bags and cans bordering the sides, a few skinny trees. The sound of birds.

Mamá was pretty sure she had a prima in Texas. Por lo menos una in Ari-zo-na too, but she wasn’t sure.

He didn’t stay out too long or too late. He was terrified of being recruited. They had already started with the beatings. Thrown rocks on his way to school. Once, a cop had watched. Arlin wondered how much it cost, to pay a cop to watch. How much he was worth. One man’s silence.

A friend explained it to him simply: “Your dad does it, you do it. Your uncle does it, you do it. Your uncle’s friend does it, you do it.” And if you didn’t, they’d rape your cousin, your aunt. Cartel, colateral.

Later, his friend stopped showing up to school. They had kidnapped his sister, then returned her. She hadn’t come back to school either.

|||

“You have the rest of the period,” the teacher said.

White rectangles lay face-up on the desks. The students bent their heads.

Arlin was translating words. He had come too late in the school year to take the test, opted out.

Salma began to rub her temples. Small circles.

“Spelling counts,” the teacher reminded them. She crossed her arms. “It’s a vocabulary test.”

Salma put her head down.

It took Arlin a while to find words in Spanish. He flipped the pages in the dictionary, the pleasant beating swish of paper rippling past his thumb. He tried to remember the alphabet song. He was grateful that he could read in Spanish.

The boys at his table were all frantically scribbling.

Salma’s narrow shoulders shook. A sound emerged, in dashes and hiccups. High, light.

Arlin stopped, putting the dictionary down. Salma’s eyes were shielded by the fan of her fingers.

“Yo,” one of the Pakistani boys hissed, his whisper low and sharp. He glared at Arlin. Quietly: “We don’t have letters in our language.”

Arlin nodded. Letras. The Pakistani boy kept glaring at him.

“No, serious,” the small boy said, slowly. He leaned over Arlin’s desk, drawing something on his paper.

Arlin stared.

“Fahad,” the boy said. “My name. My name is Fahad.”

Fahad’s name looked like the curls of wind drawn in a cartoon.

|||

The Chinese boys never talked to him. One of them played games on his phone under the desk.

When a new Chinese boy came in, the teacher sat Boqin next to him. Boqin got everything right. “Can you help our new student, Boqin,” she said, brightly.

Twenty minutes passed without the boys exchanging a word.

The teacher tried again, attempting to get the boys to overcome themselves. She squatted down, murmuring.

“I don’t speak his language,” Boqin said stiffly, loud enough for Arlin to hear.

The teacher blinked. “Don’t you speak Chinese?”

“Not his Chinese.”

Around them, the class went silent.

“Did you...use the dictionary?”

“He speaks Cantonese,” Boqin responded curtly. “Not Mandarin.”

The teacher looked at him. She nodded slowly, feigning like she understood. “Okay,” she said.

She let Boqin sit where he wanted to.

“What is Cantonese?” Fahad asked the Taiwanese girl at their table.

“It Chinese,” she explained, “but not all Chinese same.”

Salma turned around from her table, hearing her. “They don’t have Arabic from Yemen,” she said. The Taiwanese girl looked at her kindly. Salma kept her dictionary closed too, even though the teacher had yelled at the class yesterday for not translating enough vocabulary.

“Por lo menos,” Stephany whispered, leaning over to Arlin, “all Spanish is the same.” Arlin smiled. For some reason this made him proud.

|||

One blond girl spent all day doodling Manga. Arlin wondered where she got her books. In Honduras, he had learned English by watching cartoons.

The teacher gave her a Russian dictionary. The girl didn’t touch it.

One day she came in with brown ink drying on her wrist. The small hand reached out, received the failing grade the teacher handed her. Arlin watched. La rubia didn’t seem to mind the F inscribed across the page.

“Amina,” the teacher said.

The teacher had came over quietly, when they were all writing down what they had gotten wrong. I Would Like to Improve.

Arlin listened, glancing surreptitiously over. “That is a nice henna,” the teacher said softly. “Did Salma draw it for you?” Salma, also, had a lattice of flowers and triangles spinning around her wrists.

“No,” the blond girl said. “It is Muslim holiday.”

The teacher fingered the Russian dictionary. “I see.”

“I’m not Russian,” the blond girl told her, simply. “My country is Uzbek.”

The teacher opened her mouth, then closed it.

“I am Muslim,” the blond girl said. She waited patiently for the teacher to leave.

|||

In Honduras, when Mamá came home she woke him up. Sometimes she brought visitors. Often, she brought visitors.

They turned on the old radio, fed it CDs. Or they threw a phone into a porcelain cup and it rang out, muggy and loud.

Mamá taught Arlin how to dance. She clapped his hands, took his hips, shoulders.

Mamá smelled of sweat, snapping gum, and he watched the golden cruz around her neck. How it bounced against her chest, shot off flashes of light.

Men brought jugs of clear guaro, the room suddenly crowded. Cheap cologne, gasoline burning up from the motos outside. The blue house filled with cigarette smoke. It drifted out of the windows, kept away mosquitos.

|||

The girl who sat at the back of the class and smelled of Vaporoo was named Camila. She was from Colombia. Her hair curled and flowed past her waist. She had large, plush lips. Green eyes.

Vaporoo was how Arlin knew she was Latina, even though she was as pale as Stephany.

“She told me to do something bad,” Stephany said. She was staring straight ahead at the chain netting. Two staircases, at the ends of the school building, were fenced in this way. Allegedly to keep the steps intact, kids from falling. Chips of red paint flaked off the banister, making delicate piles on the steps. Arlin thought, not for the first time, how poor los status unidos actually was.

He leaned on the hard netting, keeping himself still. They were skipping class. He relaxed his posture, made himself small. Approachable.

Stephany was silent. Arlin couldn’t tell if she was waiting for him to ask something, or if there was nothing more she had to say.

|||

Some days, Arlin had helped Darrel paint. Stretch up tall, roll the big roller paint brush down, pat it into the paint. Rub the aluminum pan where the color pooled in a corner. Try a sip of Darrel’s beer as he dozed in the shade. Other days Arlin would walk around, talk to the viejitos. It was true that the old ones were the last unafraid to sit out on their steps, in front of their homes.

A lot of boys would just jump him. It was hard to gauge whether it was safer at night or in the day.

Three times Arlin was held up in a sweaty armpit, a bony forearm choking him, his face suddenly thrust to the sky. Bright blue cut by a tan jaw.

“Y porque no luchas por tu Mamá, cabrón?” a hot, breathy voice hissed into his ear. On his neck, Arlin could feel the ridges of a blade.

Mamá had yelled at him.

“Y crees que tener amigos es fácil?” He couldn’t have friends, he decided. It wasn’t safe.

One time, it had been a girl who had pummeled him. Pummeled him, kicking him straight in the nuts first and then repeatedly after. She beat him for all he had. Didn’t say a word the whole time.

Anyway, the friends he made always moved.

|||

Boqin threw a chair.

No one expected this.

“Why,” he shouted, frustrated. “WHY ‘the’, WHY ‘a’? AN?” He yelled. “WHAT IS ‘AN.’ ”

His paper was marked with blue.

“It’s just an article,” the teacher told him, trying to calm him down.

There must not be article in Chinese, Arlin thought.

“WHY,” Boqin screamed. His long black hair was greasy. For the first time, Arlin noticed bruises. His clothes were too small.

“Boqin,” the teacher said.

Boqin stared at his paper. His expression sickened Arlin.

It was a look of pure hatred.

Boqin sat down. Than he stood up, walking out the door.

“In Uzbek, they neither have articles,” the blond girl whispered to Stephany.

Arlin listed Spanish articles in his mind. El. La. Los. Las. Having one article actually made Inglés easier.

“In China,” the new Cantonese boy said, slowly, trying to explain as the teacher rushed out, “We work hard. Even, in…” He paused to think. “Gym.” He pantomimed running in his seat. “Many far. More hard.”

Arlin had never had a gym class before coming here. He stopped going to school in third grade.

|||

“Okay,” Darrel said. He put his eye to the gun, then lowered it down. His arm was straight. The metal gleamed as it passed from Darrel’s hand to Arlin’s.

“Shoot.”

Arlin was afraid of the noise.

“No, no.” Darrel grinned. His eyes filled with something. “It has a silencer.”

Darrel also taught him how to slash, downward-up, to use the forearm crossed over the chest as defense, instead of leaving the ribs exposed like un maldito idiota when throwing up the aiming arm, revealing the stomach before bringing the knife down. That’s just the way you did it with a switchblade, the fastest way, since your thumb was already on the handle like it was pressing a goddamn picture on your phone and not curled around a pinche knife. Try again. Rápido, con fuerza. Like dragging down the roller paintbrush at work, cabron. Natural. Es fácil. These were the exercises Arlin remembered.

|||

“My math is really good,” Fahad bragged. Across the dining room table Arlin rolled his eyes. He scanned the homework, than spun the sheet away from Fahad to face him, copying rapidly.

Fahad just grinned, licking the last bit of Mott’s applesauce from his spoon. It was his favorite American food. Arlin quickly started copying answers.

“In Pakistan we do math all day,” Fahad said. He leaned back in the chair. He loved having Arlin over, loved showing off. “No, seriously,” he repeated.

“You’re being a fuckin’ nark.” A tall boy loped in, music beating thinly out of his earphones. One bud swung loosely as he bent down, opening the fridge.

“What’s a ‘nark,’ ” Fahad asked dryly.

“You need to study your English, Fahad,” his brother chided, grabbing the half-gallon of milk and standing up. He turned to the cupboards, unzipping his long black coat. Fur along the hood. “Where’s umi.” The tall boy poured cereal into a bowl. Flakes clinked against the sides.

Arlin couldn’t remember if Fahad’s brother was in highschool. Fifteen was much older than thirteen.

“Getting dinner,” Fahad said. Inspired, he took the full Mott’s jar in two hands, dumping it all out into his own bowl. Then he put it in the microwave, punching in a few numbers.

“You’re so extra Fahad,” his older brother said, watching him. He crunched a spoonful of Cocoa Puffs.

“Extra what,” Fahad asked, irritated.

His brother laughed. “Yo,” he said, swallowing, ignoring Arlin completely, “I’m glad you killed that shaqiq,” he waved a spoon, “because I just bought a whole pack of little lunch Motts for the sisters.”

“What?” The microwave beeped. The room smelled of hot applesauce.

“You ate the whole thing,” Fahad’s brother answered calmly. “That’s not fair.”

“They hate Motts!” Fahad cried, livid. He shot up. “Give it to me,” he demanded. His small frame did him no favors. He looked like a child. “You’re just triggering me.”

“Nice, Fahad.” His brother grinned at Fahad’s attempt at slang.

Fahad darted to the fridge.

“Are you lying?” he demanded, his face buried behind the door.

“I’m broke, maynn.” Fahad’s brother smiled innocently.

“What the fuck, Ejaz!”

Arlin tried hard not to laugh. Once, when they were at the park, Fahad had yelled in his defense. “He’s not Mex-i-can mothafucker! Go to school!” Fahad had screamed after the boy, long after they lost the soccer ball. Little Fahad shouting this had seemed like the funniest and also meanest insult Arlin had heard.

Fahad’s brother slowly pulled out a small plastic container of Motts from his coat. “Chill.” He held it up in the air.

Fahad was immediately at his side, grabbing hold of his arm.

“Chill,” his brother repeated. He palmed Fahad’s head easily, pushing him away with his hand. He stood up, Fahad glaring at him. “I’m savin’ this for later, when I get hungry.” The tall boy’s hair was slicked artfully back, and he wore a multitude of chains. “You’re such a fatass you won’t get hungry later, so.” Arlin told himself that half of the chains were fake. No one would wear that much money.

“We gotta do laundry,” the brother announced abruptly. “Okay?” He looked at Arlin, suddenly a pillar of authority. “Get the laundry bags. Bring homework.” Fahad looked down at his bowl, ignoring him. “Now.”

Outside Arlin remembered how much he hated the fucking cold. Around the lumpy bag of laundry, his fingers turned to ice.

“Hold your breath,” Fahad’s brother yelled out suddenly, “We passin’ a precinct boys!”

Arlin took a breath and held it. They strolled quickly past. He glanced up, confused. He thought people only held their breath when crossing cemeteries.

Fahad’s brother caught his look and laughed. “You never know how many people died in there, my nigga.” He clapped Arlin on the back.

Arlin would remember took look up the word “ni-ga” later.

|||

Pop-Eyes: Chicken Dinner, $5.29

KFC: One Piece Meal, $5.49

McDonalds: Big Mac Burger, $3.99

Burger King: Whopper, $4.19

Wendy’s: Burger, $4.19

None of them had fríjoles.

|||

“Did you think he did a good job?” The teacher smelled clean. Sweet.

Arlin blinked. “Ah…” He thought about the boy in the book. “Yes.”

“Why?”

Arlin chewed the inside of his cheek. The teacher was very close to him. Fahad snickered.

“He was good,” Arlin said, ignoring Fahad. He tried to elaborate, hunting for the words. “He did de right ting.”

“How do you know?” The teacher was gentle. She looked at his page.

Arlin gave up. He shrugged.

“Do you know what this is,” his teacher asked him. She bent down, eye level with his desk. Leaned towards him on her elbows, irretrievably close. He could smell her shampoo.

“Do you know what this is?” the teacher repeated. She was tapping his paper, an immaculate white hand.

Arlin nodded.

“What is it?”

He smiled. Looked down.

“We have a word for this in English,” his teacher said. Her finger swept over the paragraph.

“Evidence.”

Arlin nodded.

“Can you say it?”

“Ev...e...dance.” He said it slowly.

“You can tell me anything you want,” his teacher explained to him. “But I don’t have to believe you.”

She tapped the page again. “Ev-i-den-ce,” she said. “You have to prove it.”

|||

There were two routes from the store to the house. The backway and frontway. Sometimes Arlin skirted the walls, sometimes he didn’t. The sun was high. He slurped the bag of pink juice. Maracuyá.

He froze.

Across the street, two men burst into the blue house.

A shout. Darrel.

Clatter. The men were not afraid to make a scene.

Arlin couldn’t see into the small window.

From the side of the road, a gunshot.

Arlin stood perfectly still.

Realization flooded his body. Darrel was dead.

In his hand, he held a bottle of milk. Carefully, Arlin flattened himself against the wall.

|||

Amina was in detention for the week.

Five boys had shown up to the nurses office that morning, sick and reeking of vodka.

Blond, Uzbek, Muslim Amina had, ingeniously, sold them alcohol in Poland Spring water bottles.

Passing Arlin in the hallway, she asked for colored pencils. The teachers had taken them from her. In addition to her folder of Manga sketches.

Whether or not Amina had learned the trick from her older brother, Arlin had to admit he was impressed. La rubia may have been failing, but she was quick with money.

|||

Mama left to visit the man in the apartment downstairs. When she came back upstairs, she was sleepy.

The man had given Arlin an old red nintendo and a handful of games. At first, Arlin didn’t play. He stared at it, angry at the scuffed corners, the way the man had opened his hand, how the device had laid faceup on his massive palm.

Now he and Fahad passed it between them, yelling. They learned English from the subtitles.

|||

“I don’t want to,” Stephany began. Arlin saw her chin tremble, just a little. Something passed down over her eyes. November sky, an unbroken white. A sheet of cloud.

She had been smoking a cigarette when he walked up to her.

“I found it,” she said.

He didn’t comment. He knew when someone was lying. Stephany had a bag of cold McDonald’s at her feet. Arlin tried to think of a McDonald’s that was close by. Took a drag when she offered. He always liked the smell better than the taste.

“I really don’t want to,” Stephany said again. This time she was crying for real. She shoved a pale fist over her cheek, then pressed her yellow nail under the sallow of her eye, her eyes rolling up. Carefully she wiped off any residual mascara.

“I’m moving to el Bronx,” she told him. She looked up again at something Arlin couldn’t see. “I don’t want to be part of a gang family.”

They watched the cigarette burn away in silence.

|||

After Stephany stopped coming to school, Camila started talking to him.

“Oye,” Camila said. She watched him over a carton of cafeteria milk. “You really think it’s better over here? Than back there?”

She was asking Arlin in Spanish, and Fahad looked at him uneasily. She wasn’t talking about where they were sitting.

“It’s not, motherfucker.” This in English. Camila sipped her milk.

“She likes you,” Fahad told him.

|||

Mamá’s teeth chattered.

“Que frío,” she said. She repeated it, holding him close. Her small hands curled into each other, then pushed into the radiator. Knuckles straight into the hot metal. “Que frío.” Mama hadn’t painted her nails for days.

Mamá had been afraid to shower. So was Arlin. He tried to remember ever feeling cold water. Maldito desagradecido. He had been ungrateful.

They had not had heat for three days.

|||

Camila had torn a chunk from Stephany’s hair.

“FUCK YOUR COUNTRY,” she had screamed. In the park, with the sidewalk chipping away.

Arlin thought she had moved already.

Kids weren’t playing now, on the old squeaky swings. Arlin did not like the metal, here or on the subway poles. It reminded him of the taste, being shoved up against it. A mouthful of something sour.

Camila pushed Stephany to the ground.

Stephany grabbed her arms, yelling, kicking Camila’s stomach with her knee. The girls wrestled on the pavement.

No kids chiquito here. Little kids needed someone to watch them at the park, and now was the time older siblings were in school.

“YOU’RE FUCKING JEALOUS YOU CUNT,” Stephany screamed back. She screamed it in English.

Camila slammed Stephany’s head into the concrete.

There weren’t many parks, and most of them had fences.

Arlin had come late.

Two men pulled the girls apart. The girls’ brothers.

The two men looked at each other. Something flashed between them. They recognized one another.

Their sisters screaming, screaming. Screaming.

Silently, almost methodically, the two older boys hauled the girls apart. The nuances fell away in that instant, the different families pulling from each other in almost perfect symmetry. A mirror image, split in half by the pavement, the pavement widening, widening between them as the girls kicked the air on either side, high, can-can kicks. On either side, a tall dark boy with dark hair; at his knees, clutching him, a screaming light-skinned girl. Her sneakers flapping up, hitting the ground. Shrieks clear in the stillness, the ribbon of pavement swelling thick until the the girls were flushed away completely, shuttered into the shoulders of their brothers, tucked behind the brick corners of this many edged city-- two sets of siblings, cleanly disappearing. And the sky, swept new and silent and plain again, smooth and white as though nothing had happened. What had happened?

Behind the chain fence Arlin shivered.

He missed trees.

|||

Their house had been blue. Topped in bright, rounding orange tiles. It had been their house all of Arlin’s life, all of his mother’s and Darrel’s and Emely’s life, and all of their parents’ lives, too.

“I don’t like being scared,” Luisa said to Arlin’s mother. Arlin’s tía, or in practice anyway. The women were sitting on the steps, shading their eyes. Luisa’s hair was long and twisted up behind her, her ribbed tanktop tight over the pregnant belly. “It’s exhausting,” Luisa continued, letting smoke fall from the side of her mouth, waving her cigarette at Arlin as he passed through the door frame.

His pockets were stuffed with chicle and in the heavily draped room Arlin would pop off his shoes, the house dim and cool. Fling himself on the couch, sighing deeply. Que calor. What heat. Outside, his mother and her friend painted their toenails, and Arlin would nap and nap and nap. Until Darrel got home. The women would chat long into the dark, and when Arlin woke up again, they would be cooking at the stove, and sometimes someone would drop by, with some things they were leaving behind--pots, tools, clothes--because they too would be heading up North, try their luck with La Bestia, couldn’t take it anymore, just couldn’t--but right then Arlin was listening to the cicadas with his eyes closed, his head sunk in the couch cushions, blanketed in smoke, the smell of something frying on the stove.

|||

Salma was leaving.

Amina, so much littler and with a thick purple headband, hugged her for almost three minutes. Crowded by the classroom door waiting for dismissal, Salma’s thin arms clutched the little blond, enveloping the long braid. She shut her eyes, rested her chin on the small yellow head.

When Salma looked up at Arlin, eyes full of tears, he felt a little guilty about how beautiful she was.

“Why are you go-ing,” he fumbled. He didn’t know how to say goodbye. He held onto the straps of his backpack, elbows pointed awkwardly outward.

Salma hiccuped. She inhaled. “Em…” Amina darted over, bringing the cardboard tissue box. Around them, students bubbled up, fell away excitedly. Viernes. Friday.

“I am going back to my country,” Salma said, so softly Arlin barely heard.

He just nodded, feeling like an idiot.

She tried smiling. “I will miss school.”

Fahad avoided them, lingering in the back of the line. Arlin glanced at him. Fahad knew more, and he also, Arlin knew, would not talk about it.

The bell sounded, long and clear over the speakers. Salma turned, waving over her shoulder at their teacher. “Bye,” she called, ducking quickly. She hadn’t told the teacher that she wasn’t coming back. For weeks, teachers would call a number that rang and rang on an abandoned cellphone.

|||

Mamá was crying. She smoked the cigarette in silence.

Arlin didn’t ask. He knew she had lost her job.

Gingerly he unwrapped the honey treat Fahad had given him. Arlin was addicted to it, the syrupy, flakey stickiness that he couldn’t pronounce. He had always preferred sweets to salt, even when his family doused meals in pepino and vinagre. Fahad had brought him two squares in lunch. Grandmother, jida sent them, Fahad said, grinning. She likes you.

Arlin hadn’t minded helping the old women. He could wash dishes forever, hot water running over his hands.

“Cómo estás, hijo?”

Arlin presented his mother with a sheet of a paper and the gluey square. The syrup had hardened with the cold.

A+. Great work! He translated the red ink and Mamá smiled, covering him in kisses.

“Claro,” she beamed. My son. Por supuesto. Of course.

Arlin wondered if he was old enough to get a job.

|||

“You know your dad?” Camila asked, after a pause. Her hair smelled strongly of gel.

They sat on the swings.

“No,” Arlin said.

“I did,” she said.

Arlin took care to keep his gaze somewhere neutral. He didn’t want to know his dad.

Camila offered him a Poland Spring bottle and Arlin took it cautiously, unscrewing and sniffing. Just water.

“He got deported.” It was a line Camila knew how to say in English.

She seemed sad. “Lo siento,” he said, quietly.

“I feel you,” she answered. Arlin looked at her. “Siento mean feel in English,” she explained, not without a flush pride, “not just ‘sorry.’ Siento mean sorry and feel in Español, but in English there is two word.”

She grinned and Arlin grinned back. He didn’t know what else to say.

They stared out for a while. An older lady with a bright handkerchief around her head passed, waddling slowly, pushing a stroller in front of her. She was speaking on a cellphone in language Arlin had never heard.

“I’m not really Colombian.”

Arlin turned to her.

“I was born there, but we moved back to Venezuela.” She twisted the bottle in her hands. “That’s where my family is from.”

“Really?” Arlin asked. He seemed to remember the countries were close.

“Yeah.” Camila paused. It had been bothering her. “I don’t really remember Colombia. Venezuela was bad.” She said this in English too. “It sucked.”

Arlin just nodded.

Camila wasn’t looking at him. Her eyebrows were drawn. “I want to remember Colombia.” She narrowed her eyes further. “Fuck Venezuela.” And then turned to face him once more, seeking confirmation. “Isn’t where you’re born where you’re from?”

|||

In the vacant lot, along the abandoned strip of a gas station, Arlin and Mamá boarded a bus. On the bus men pulled caps low over their eyes. The windows had a clouded sheen. The seats were worn, faded navy.

After a week Arlin would be sick them. Prefer to piss outside, behind a building rather than in the small, shuddering toilet that did not flush. After a week, Arlin and his mother would arrive in Woodside, Queens.

|||

The day they left the blue house, Mamá kissed her two fingers and touched the door. They didn’t say a prayer. They left the picture of the Virgin Mary on the shelf, along with the cross. Mamá kept the chain she had from her mother, and Arlin kept Darrel’s. These were the only blessings they needed.

|||

A few days later, it was supposed to rain, and because it was supposed to rain, no one was at the park.

On his fourteenth birthday, beneath a plastic slide, Arlin lost his virginity to Camila Michelena.

After, she bought him a lighter. She placed it on the counter, and the man behind it, his hair slicked smooth, regarded her. She stared back. The man gave her a slight nod.

She swiped the green lighter up, dropping it in Arlin’s palm.

|||

The most beautiful view in Honduras overlooked the mountains.

Not up them, but down them. An orange road curved along the bend, the cliff steep and crumbling into sand. Held back by a low, metal rail. Arlin knew at least three motociclistas who died this way. Over the cliff, into the ravine. La selva.

The only way to get to the spot was to pass the cemetery, which wasn’t a cemetery really, but a big white stucco building. The bodies were slotted in high cupboards, or stacked drawers, depending on how you thought about it. A painted wooden panel slid over the opening, the name and date scrawled in pen. Sometimes pencil. Like Darrel’s.

Past this, past the patio steps that opened up to that spooky place, there was a trail. A fingerling path that twisted down into the deep green jungle, into the hissing mosquitos, the jumble of giant, shiny leaves.

Somewhere in there, cocaine was being cooked. Methamphetamine. Guns, hidden and shipped. Women, hidden and shipped.

It wasn’t a secret. Everyone knew this.

But the view. It was beautiful, lush and wild, and young lovers were known to lean on the highway railing, dangle their feet over the edge. Kiss to the sound of purring cicadas.

And this would show up in his dreams, as often as his nightmares, this place, so close to death, so close to life. Mama’s breath in his ear, but we made it, mijo, Emely didn’t but we did, we made it and Arlin would wake up without a sense of language, of place, and memory rinsed over him and then vanished, so quickly, like a coin turning in the sun, flipped down on the back of hand. Some faceless child’s laughter, a lost bet, a game, sunlight, morning, morning rising up like any other, the memories and the dreams all the same.